“Core 5”: A Bold Vision for 21st Century Diplomacy?

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor starts in Kashgar, China, and ends at Gwadar Port, Pakistan, with a total length of 3,000 km, connecting the Silk Road Economic Belt in the north and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road in the south, is the key hub of the North-South Silk Road, a “four-in-one” corridor and trade corridor covered by roads, railways, oil and gas pipelines

Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, people don’t criticize themselves for anything, no matter how wrong it may be.

The diplomatic relations between the Sultanate of Oman and the Republic of India are characterized by a deep-rooted historical connection, strategic partnership, and a shared vision for regional stability and economic cooperation.

From a worldwide perspective, desertification refers to the land degradation in some regions caused by various factors, including climate variability and human activities.

The European Union (EU) is a supranational organization that has gradually emerged as a significant player in global politics, with a foreign policy that reflects its commitment to multilateralism, peace, and stability.

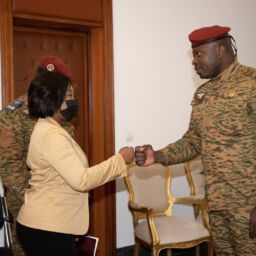

The Burkina Faso coup on January 24 resulted in the removal of President Roch Marc Christian Kabore

In a decisive response to recent provocations, Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov has announced the launch of an investigation by the Russian Investigation Committee

On 15-16 November, after almost a year in the making, the G20 Leaders’ Summit, under the Indonesian presidency

It is quite amazing to witness porn star Stormy Daniels teach morals and legality in an age when sensationalism frequently takes precedence over content.

CAIRO – In a statement that could signify a potential shift in the geopolitical dynamics of the Horn of Africa, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.

The President of Tunisia, Kais Saied, rejected the “dictations” of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an institution that conditions the granting of a loan to Tunisia on economic reforms and the elimination of public subsidies.

The African Transformation Movement (ATM) has ignited a national conversation about identity, heritage, and the future of South Africa by advocating for the country to be renamed the “Republic of Azania.”