New Dynamics in Global Trade U.S.-Vietnam and U.S.-Canada Developments

Photo: Reuters

Photo: Reuters

Tense situation in North Korea

Amid the sky-high temperature rise and the cramming of urban space, green cities have become a key strategic approach to sustainable development.

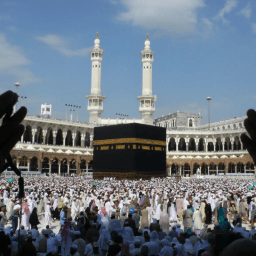

As the sun sets on February 28, 2025, millions of Muslims around the world prepare to usher in Ramadan, the sacred month of fasting, prayer, and reflection.

In a world often marked by division and misunderstanding, Pope Francis’s historic visit to Mongolia in 2023 served as a beacon of hope and unity.

As the world turns its attention towards Asia, U.S. President Joe Biden is set to arrive in Hanoi, Vietnam on Sunday afternoon, marking a significant step in the administration’s efforts to strengthen bilateral

On Friday, Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida reaffirmed his country’s willingness to engage in high-level talks with North Korea “without preconditions”.

The Kingdom of Tonga, known as the “Friendly Islands,” is a Polynesian sovereign state and archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean.

The Republic of Kiribati, or Kiribati for short, is a Pacific Island nation. It has a land area of 811 square kilometres and a maritime exclusive economic zone of 3.5 million square kilometres.

As the world grapples with the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, world leaders gathered at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, to deliberate on the state of the global economy.

On Saturday, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan signaled that Turkey could potentially “part ways” with the European Union (EU) if necessary.

The story of Haiti’s independence struggle is a tribute to the unwavering spirit of a subjugated people who rebelled against their colonizers and became part of history.

Prerequisites for price discrimination

The numbers show how bad the economy went in the period when we expected it to go badly. They offer some surprises about the countries that are most affected.

An exceptional case was brought to light the other day by the Romanian prosecutors. An editorial from Solid News Romania