Oman, the Pearl of the Middle East

Despite is one of the least internationally visible countries of the Arabian Peninsula, Oman is an important player both from a geopolitical point of view and in terms of regional balances. The small Sultanate occupies a strategic geographical position which leads it to control, together with Iran on the other side of the Persian Gulf, the vital Strait of Hormuz, an artery of primary importance for trade routes to and from the countries bordering the Gulf and, above all, for their hydrocarbon exports.

Oman is a member of the organization of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and has a privileged relationship with the United Arab Emirates (Uae) which surround two exclaves of Oman: the territory of Madha and the Musandam peninsula, located right on the Strait of Hormuz.

The Sultanate, like most Arab countries, has no diplomatic relations with Israel and, on the other hand, is connected with Iran, especially by the common management of the Strait of Hormuz.

The long diplomatic tradition has allowed Oman to intensify relations with the major Western powers – especially the USA and the UK – despite good relations with Iran.

The most problematic neighbour in Omani is Yemen, with which they concluded an agreement on the definition of the common border only in 1992. In order to protect the security of the country, Oman actively supports the stability of its neighbouring country and keeps strict border controls in place.

From the institutional point of view, Oman is an absolute monarchy, with a sultan system at the head of which, since January 2020, there is Haytham bin Ṭāriq bin Taymūr Āl Saʿīd. The sultan has very extensive powers: he is head of state and government, appoints the executive and holds the offices of minister of foreign affairs, defence and finance. The country also has a bicameral parliamentary system, consisting of an Advisory Council, called Majlis al-Shura (since 1990), and the Council of State, Majlis al-Dawla (since 1997).

The first of these two assemblies has 86 members and, since October 4, 2003, is elected by universal suffrage (from the age of 21), while the council of state has 83 members appointed directly by the Sultan.

After five months of protests in early 2011, some reforms were introduced.

The most important one concerns the Majlis al-Shura, which has acquired legislative powers.

These reforms have been interpreted as the beginning of the transition from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one, although there is still a long way to go.

The Omani system does not allow the establishment of political parties and, as in many other Arab realities, the relationship of trust between rulers and subordinates is mainly based on tribal relations.

In recent years, the government has taken a reform path in health and education, where the country has made significant progress: average youth literacy stands at 97%, with a slight imbalance towards women.

Oman has never had a proper constitution.

In 1996, however, Sultan Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd issued the so-called Basic Law, which defines the institutional and legal characteristics of the country and defines that Islamic law, Sharia law, is the only source of law and Islam is the state religion. In the political landscape, there is no place for the oppositions organized through parties and the internal dialectic is almost non-existent.

Although the Sultan is a ”beloved” figure by the people, in recent years there has been no lack of criticism for the repressions that have crushed some free opinion demonstrations.

In June 2012, the authorities issued several arrest warrants and sentences against bloggers and human rights activists.

In March 2013, surprisingly, the Sultan brought his official apologies to the condemned. But the crackdown on free speech was later resumed with further arrests.

Women’s rights and gender equality have improved in recent years. In 2004, for the first time, the Sultan appointed two women ministers to his new government.

The sultan, therefore, holds absolute power, he is both monarch and head of state. He therefore obviously has the most powerful position in the country. The sultans of Oman are members of the Al Said dynasty, which is the ruling family of Oman since the mid-18th century. From a contemporary point of view, in order to better understand the current dynamics of Oman, it is appropriate to begin to focus on Saʿīd bin Taymūr.

The Sultanate of Saʿīd bin Taymūr (1932-1970)

Saʿīd bin Taymūr after the abdication of his father on February 10, 1932, became the new Sultan at the age of 21. He inherited a country heavily indebted to both the United Kingdom and British India. In order to break away from the British and maintain autonomy, his country needed to regain economic independence. Therefore, starting in 1933, he took control of the state budget.

Once he became a sultan, Saʿīd bin Taymūr maintained friendly relations with the United States of America, while during the Second World War he readily collaborated with the British.

Several Royal Air Force landing fields were built between Salalah, Dhofar and Mascate, which allowed that the supply channels between India and the Allies remained open.

In 1951 he assured the recognition of his independence by the British. However, he also had to face strong internal opposition from Imam Ghalib Alhinai, a religious leader of Oman, who claimed the power in the Sultanate for himself.

The revolt of the Imam in Jebel Akhdar was suppressed in 1955 with the help of the British, this caused the anger of Saudi Arabia, which supported the Imam, and also of Egypt, which considered the British involvement not favourable to the cause of Arab nationalism.

In 1957 these two countries supported a new revolt by the imam, which in 1959 was suppressed like the previous one.

From an economic point of view, Oman’s oil wealth would have allowed Saʿīd bin Taymūr to modernize his country. This did not happen in fact as the years went by, Saʿīd bin Taymūr became increasingly estranged from his people and his country. Although in 1965 he was able to conclude agreements to export oil to Iraq, Iran and the UK, he did little to improve the lives of his people. The benefits of this agreement would only be achieved after his deposition.

In 1965 the province of Dhofar rebelled against the Sultan, this time with the support of China and some Arab nationalist states. The following year there was even an attempted murder against him. These facts had a significant effect on the Sultan, making him even more intransigent towards all his subordinates, establishing many prohibitions such as smoking in public, playing football, wearing sunglasses or talking to anyone for more than 15 minutes.

Because of its conservative policies, Oman had an infant mortality rate of 75% and venereal diseases, malnutrition and trachoma were widespread throughout the country.

In addition, no education policies were implemented, there were only three schools in the whole country and consequently, the literacy rate was very low, 5%.

On 23 July 1970, Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd the son of the Sultan, successfully executed a coup d’état against his father with the help of the British Government and his uncle. In the brief struggle, Saʿīd bin Taymūr injured himself while he was trying to arm a gun. After receiving medical treatment in Bahrain the former monarch moved into exile in the United Kingdom, where he died on October 19, 1972.

The sultanate of Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd (1970-2020)

Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd inaugurated his reign on July 23, 1970, in Mascate.

The Sultan ruled as an absolute monarch, in a condition similar to that of the sovereigns of Saudi Arabia. His personal decisions were not affected by any change by the other members of the royal family of Oman. Instead, government decisions were subject to the consent of federal, provincial and local institutions and tribal representatives (some critics claim that Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd exercised de facto control over this process).

Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd allowed parliamentary elections, in which women were put in a position to vote and stand as candidates and were also promised great openness and participation in the government.

However, Parliament lacked real political power. Despite the fact that the Sultan had been forced to surrender to it an exclusively advisory function, legislative power.

This was to curb the dissatisfaction that broke out in some protest demonstrations: according to the official ONA agency, the Sultan gave “legislative and supervisory powers” over government action to the “Council of Oman”.

Compared to the standards of the other countries of the Persian Gulf, Oman guaranteed good public order (it is still today an extremely safe country), a fair economy (due to its oil production) and a relatively permissive society.

Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd worked in the process of modernization of the country through the implementation of a policy of reforms and development projects, especially in education and health, liberalized newspapers, built highways, opened hotels and shopping centres and in the eighties founded the first university in his country, the Sultan Qaboos University.

It is important to point out that today the level of literacy in the country is widespread in more than 90% of the total population.

During the Arab Spring of 2011, Oman was also touched by youth protests (50% of the population is under 25 years of age and largely unemployed) but, thanks to the high price of oil in those years, the Sultan managed to silence the riots by opening more than 50,000 new jobs in public offices, raised the minimum wage and established economic aid for the poorest 80,000 families.

It also simplified access to universities and encouraged the recruitment of local staff in the private sector.

From an economic point of view, Oman is closely bound up with hydrocarbon production. Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd had already understood that this in perspective could be a problem for the country, in fact, at the beginning of the 2000’s he launched the project to diversify the economy from gas and oil and, anticipating the Saudi one, he called it “Vision 2020”.

Unfortunately, 2020 has come and brought with it a generalized reduction in oil prices and the desired diversification is still far from being achieved.

The oil industry continues to account for 70% of government revenue, 35% of its gross domestic product and 60% of its exports, as recently noted by S&P.

The drop in revenues, due to the fall in oil prices since 2014, has caused a budget deficit of more than $10 billion per year with a consequent increase in public debt from 5% in 2014 to 50% in 2018 and a high rate of unemployment. In March 2010, international rating agencies classified Omani bonds as “junk”. In an attempt to overcome the economic impasse, a tax was launched for the first time introducing a 5% VAT.

Under Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd, Oman intertwined international relations: he ended the isolation of the country by joining the United Nations, October 7, 1971, and pursued a policy of rapprochement with Sunni countries, which led to Oman’s admission to the Arab League on September 29, 1971.

The same year Oman became independent, as from 1891 it was a state under the British protectorate.

Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd during his sultanate officially kept Oman neutral.

In fact since the eighties – when he mediated the ceasefire in the Iran-Iraq war while the other monarchies in the Persian Gulf funded Saddam Hussein’s army – Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd acted as a regional stabilizer. He tried to act as a bridge between Sunni monarchies and Shiite Iran, with the latter country he also established normal diplomatic relations, although he continued to be an ally of Western states such as the United Kingdom and the United States.

In 1979 Oman was, together with the Sudan of Ja’far al-Nimeyri, the only Arab state to recognize the peace agreement (Camp David) between President Anwar al-Sādāt’s Egypt and Israel.

Compared to other Persian Gulf states, Oman adopted a prudent and pragmatic foreign policy, always declaring itself neutral and establishing a balance between its own policy and that of the United States.

In 1981 it joined the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) but always strongly rejected the repeated attempts by the Saudi Arabian side to establish a military union between all member countries.

Two episodes could easily demonstrate Quabus’ foresight: his role in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2013 and in the Gulf crisis of 2017.

As far as the JCPOA is concerned, in fact, he showed great mediation skills: although the Iran Nuclear Deal was signed in 2015, Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd efforts to negotiate between counterparts started a long time earlier. An example of these efforts is certainly the historic meeting between the former Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif and former US Secretary of State John Kerry, held in the capital Muscat in November 2014.

The second example in which the Sultan showed great diplomatic skills concerns the period of high tension in the Gulf in 2017, especially between Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

On this occasion, Oman was the only country in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) that did not take sides against Qatar.

Oman’s role in diplomatic relations was so important that it was able to join both the Saudi-led Gulf Cooperation Council and maintain excellent relations with Tehran at the same time. At the same time, Oman also became a member of all major international organizations, FAO, WTO, UNESCO, UNIDO, Interpol, Arab League, Non-Aligned Movement and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

The line of succession to the throne of Oman follows the criterion of the Salic law.

The throne, therefore, belongs to the eldest male son of the Sultan. In the absence of a male heir, the reigning sultan may appoint his successor: a brother or other male relative among the descendants of the sultan Sa’id bin, who reigned until 1856 (the year of his death). Sultan Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd, however, had no sons and had indicated that, after his death, the royal family would agree on the name of his successor.

When the sultan died in January 2020, the closest relatives of Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd were the three sisters, followed by some elderly paternal uncles and their families.

The successor should have been the prince cousin Ṭāriq ibn Taymūr Āl Saʿīd – following the line of primogeniture – but this did not bind in any way Qabus, who never publicly chose his heir, distinguishing himself in this from other sovereigns of the area.

The power was instead given to his cousin Haitham bin Tariq Al Said, Minister of Heritage and Culture and Undersecretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for Political Affairs (1986 to 1994), and subsequently appointed Secretary-General for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1994-2002).

The new Sultan Haytham bin Ṭāriq bin Taymūr Āl Saʿīd (2020-current)

On 11 January 2020 Haytham bin Ṭāriq bin Taymūr Āl Saʿīd became the new Sultan of Oman.

In his first public speech, after taking the oath, he assured that he will maintain the policy of “non-interference” pursued by his predecessor, who has carved out for the nation a role as regional mediator respected by the international community.

He also added that Oman’s foreign policy will be non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, respect the sovereignty of nations and promote international cooperation.

Being a neutral country can be a great advantage in an attempt to attract foreign investors and thus also discover a new role in the economic environment.

What is certain is that Haytham bin Ṭāriq bin Taymūr Āl Saʿīd inherits a rather negative economic situation.

Economic growth is close to zero and foreign debt continues to grow.

The World Bank estimates that in the long term the economic performance of Oman is substantially negative in fact the GDP growth, from 2012 to date, has fallen by about eight percentage points, while the deficit is at 10.9%.

An even more critical figure is relative to the debt of public finances, as I wrote earlier, which reached 53.5% of GDP (in 2014 it was only 5%).

According to the analysis, this means that the country lacks the economic tools necessary to face the current difficulties in a harmonious way.

The delicate economic situation opens up a very clear scenario: the Sultan will need to balance both internal interests – to prevent that post-Qābūs bin Saʿīd Āl Saʿīd balance from being violated – and attract investment from outside.

It is important to remember that Haitham is particularly close to the heir to the Emirate throne, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

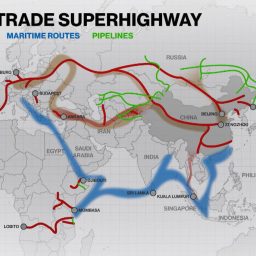

While this could facilitate the attraction of investment from the United Arab Emirates to the country, it could also expose it too much to Abu Dhabi – which has long been interested in increasing its influence in Oman. The Arab Emirates’ main focus is on the Musandam Peninsula, Omani extraterritoriality that overlooks the Strait of Hormuz and also to connect the southern ports (String of Pearl’s program), the series of ports that the Emirates intend to build from the Gulf to the Horn of Africa to the Mediterranean and integrate it with the Chinese Belt and Road. It should be noted that China has invested 10.7 billion dollars in the upgrading of the port of Duqm, in southern Oman, and, in parallel, the UAE is contributing to the construction of a 1,200 km high-speed railway line, which it will connect Duqm with the Emirates and the rest of the Arabian Peninsula.

Muscat has always been a neutral territory, able to move in the complicated regional diplomacy also because it has always been far from important constraints. This dimension is also recognized by Washington, which in fact uses Oman as a channel of communication with Iran – a way also appreciated by Tehran, as I said before.

This role has a central political value in the intra-middle eastern dynamics of the present and future, which would risk deteriorating with exposure too close to the United Arab Emirates.

The Emirates, in fact, have been the bearers of an aggressive foreign policy towards Iran, on which Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan has also moved his Saudi colleague, Mohammed bin Salman Āl Saʿūd: a policy that Abu Dhabi is currently managing without pushing too much on the accelerator, given that it has reached the brink of an escalation.

One of Haitam’s goals will certainly be to move Oman away from oil and push the Gulf state towards a more sustainable economy.

In this sense certainly, his predecessor had invested and believed strongly in tourism. The increase in international arrivals, in fact in recent years had grown at double-digit rates, only in the first quarter of 2018, the Sultanate welcomed 530,758 international tourists, an increase of 41.2% over the same period of the previous year.

What is certain is that the “recent” outbreak of the coronavirus only makes the situation worse: tourism collapse, reduced air transport, prolonged lockdown in many partner countries and oil price fall.

By Michele Brunori